Finding Your Voice: the Art of Delivering Presentations

This is an extract from Develop Your Presentation Skills by Theo Theobald.

So far, the brief has been set (either by someone else or to your own agenda), you have written the presentation content, added some interesting stories and rehearsed until you feel ready to hit the stage.

Next, we come to the actual delivery of your speech, a key part of which is the sound of your voice. We hear our voice partly through our ears but also by the sound waves travelling through our skull, owing to a thing called bone conductivity. This is why when we listen to a recording of ourselves, it comes as a shock and the more we protest to those around us that it doesn’t sound anything like our voice, the more they assure us it does. So, the best thing is to get used to it.

In extreme cases, people have set about changing their voice radically. One such example was British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who in the 1970s was coached by a television producer to lower the tone of her strident voice by 46 hertz, to give depth and authority to her speech. If you too are thinking of running for office, then please feel free to take the same route; otherwise, stick with what you have got, with a few minor tweaks (see below).

Consider the following four aspects of voice, power, pitch, passion and pace.

Power

How loud or soft our normal speaking voice is doesn’t really matter.

If we remember to ‘project’ a little more on stage it has the effect of appearing confident, but in a larger room, where microphones may well be used, a quieter voice can be amplified.

Sometimes it’s more important to remember to vary the power, rather than have everything at the same volume; this makes the speech more dramatic.

Pitch

When it comes to the rise and fall in our voices, how high or low they are, the same applies as with ‘power’: there needs to be a bit of variation. Failing to do so will leave you delivering in a dull monotone, guaranteed to send your audience to sleep. Don’t over exaggerate this, but try to be conscious of using some ‘light and shade’.

Passion

Show some emotion. You can do this through your voice. The rise and fall we have just examined will happen much more naturally if there are parts of your presentation you feel really strongly about.

Pause a moment and think about the difference in your delivery if you were presenting the company’s annual results, as opposed to speaking on behalf of a charitable foundation that you support.

Now, inside your head, try to hear the difference in your voice.

Pace

Slow down! That is the general rule for the infrequent speech maker. It does require some degree of concentration, as there is a physiological reason we go too fast, especially at the start. Our natural ‘fight or flight’ response has been triggered and we have gallons of adrenaline pumping through our system – no wonder we go at it like an express train. The plain truth is, we just want to get it over with and sit down again.

Umms and errs

I have no idea why it is, but it seems to be getting harder to avoid the tons of ‘verbal garbage’ that chokes what we are trying to say in an articulate way. I have to try really hard to eliminate the ‘umms’ and the ‘errs’ – and when it comes to the ‘y’knows’, even more concentration is required.

Good idea

So far there have been a couple of nods to what I call ‘stage persona’. This is the character the audience sees and will most likely rely on a particular aspect of who we are off-stage. It’s worth reflecting now and then on how your audience sees you; if you’re happy with the ‘character’, keep playing it that way.

It takes most people a while to work out who that person is, so don’t rush the process. When you hear professional performers interviewed, they’ll quite often say that it took them a while to find the voice that’s the authentic version of them.

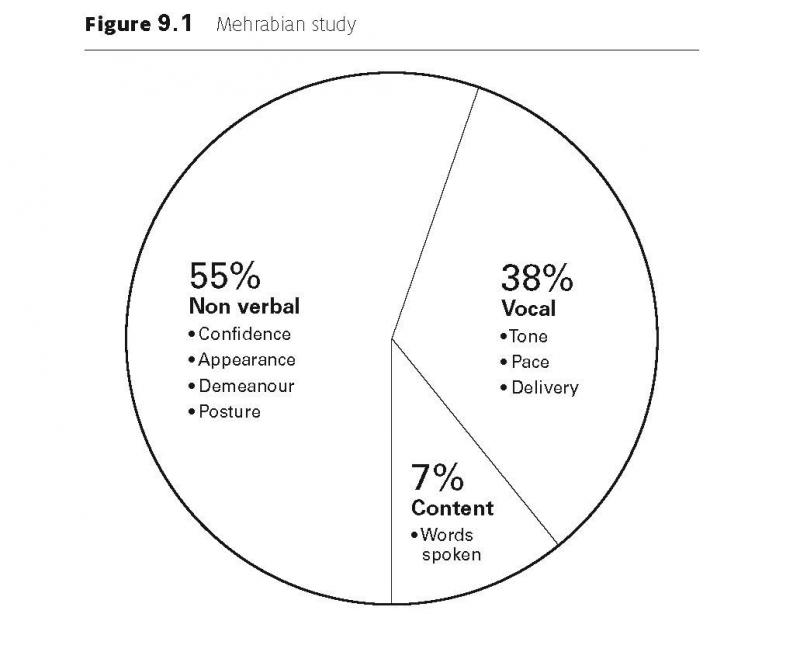

We finish this chapter by looking at the work of Albert Mehrabian from the University of California, back in the 1960s. The Mehrabian study (Figure 9.1) looked at a range of factors that might influence an audience’s ability to become engaged and interested in a speaker.

Over half (55 per cent) of the impact of a performance came from non-verbal factors, such as confidence, appearance, demeanour and posture, so think hard about these when you are reading the relevant sections in this book. Of the rest of the factors, 38 per cent fell into a category that could broadly be called ‘vocal’ – tone, pace, etc (see above). You may have worked this out – that leaves only 7 per cent of influence from the actual words spoken. So this is important stuff, but don’t lose focus, you still have to deliver the words!